Kademlia Distributed Hash Tables

I came across this exciting algorithm while watching this bit torrent series by Arpit [1] and honestly, it’s pretty exciting! I have been trying to make my own Torrent client and hopefully, will be able to publish some bare bones about its own implementation sometime in the future :D

Anyway, back to the topic at hand, Kademlia. This protocol is used to serve data in a truly decentralized peer-to-peer network. In this kind of network, from the BitTorrent perspective, the Peers will contain certain pieces of the torrent file themselves, and to connect with other peers, to fetch certain other pieces of the same file, they won’t need to talk to any central entity (in this case, Tracker).

Distributed Hash Tables

Why’d we switch to a hash table? Well, Kademlia is originally a DHT protocol that has been extended for many other use cases, and it’d make sense to understand its underlying nitty gritty.

In my understanding, a hash table is a data structure that stores key-value pairs. You can input some keys (Or rather, a hash of those keys) and store their associated value.

Now, instead of keeping all the key-value pairs on a single machine, let’s divide up all the keys and store them in separate machines, sounds good no? More machines = More keys! But it doesn’t come without its own headaches.

Headaches 😫

- How are we going to determine, which key is going to be stored in which node in such a way that one node does not have the majority of the keys, i.e. the keys are more or less equally distributed? [Ps — I will be using node and systems synonymously].

- How will one node figure out which other node in the network to talk to in case it does not have the key which has been requested by the user?

- There are a ton of nodes, no? What will happen in the scenario when the node leaves the network? How well are the keys replicated in other nodes to tackle this situation? [Of course, there is a fundamental issue here, the scenario where all the nodes leave the network, so I’ll be writing this article with the assumption that the rate of the nodes leaving the network is slow enough for the other nodes to catch up at a reasonable rate and not lose all the keys]

Consistent Hashing[2] was the first thought process about how I’d be storing the keys in multiple nodes and didn’t feel that it was much of a problem to solve.

But here comes the beautiful part -

Visualizing hash tables as a search tree

So, before we move on to the visualization, let’s set certain standards of how we are going to represent the nodes and the keys. Kademlia handled it by setting the node and key IDs to 160-bit integers (in the event the IDs are > 160 bits, a collision-resistant hash function is used to map the ID to 160 bits, original researchers used SHA-1 hash to achieve this).

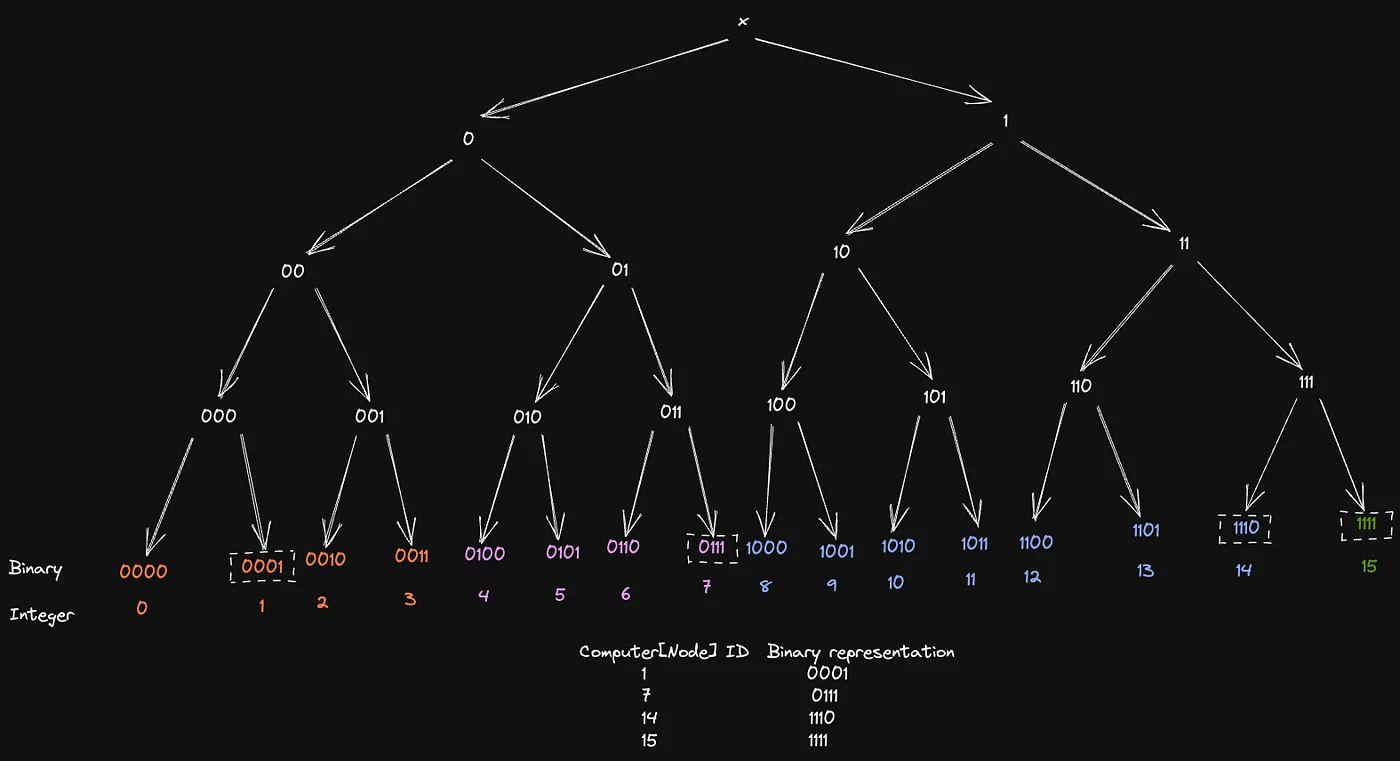

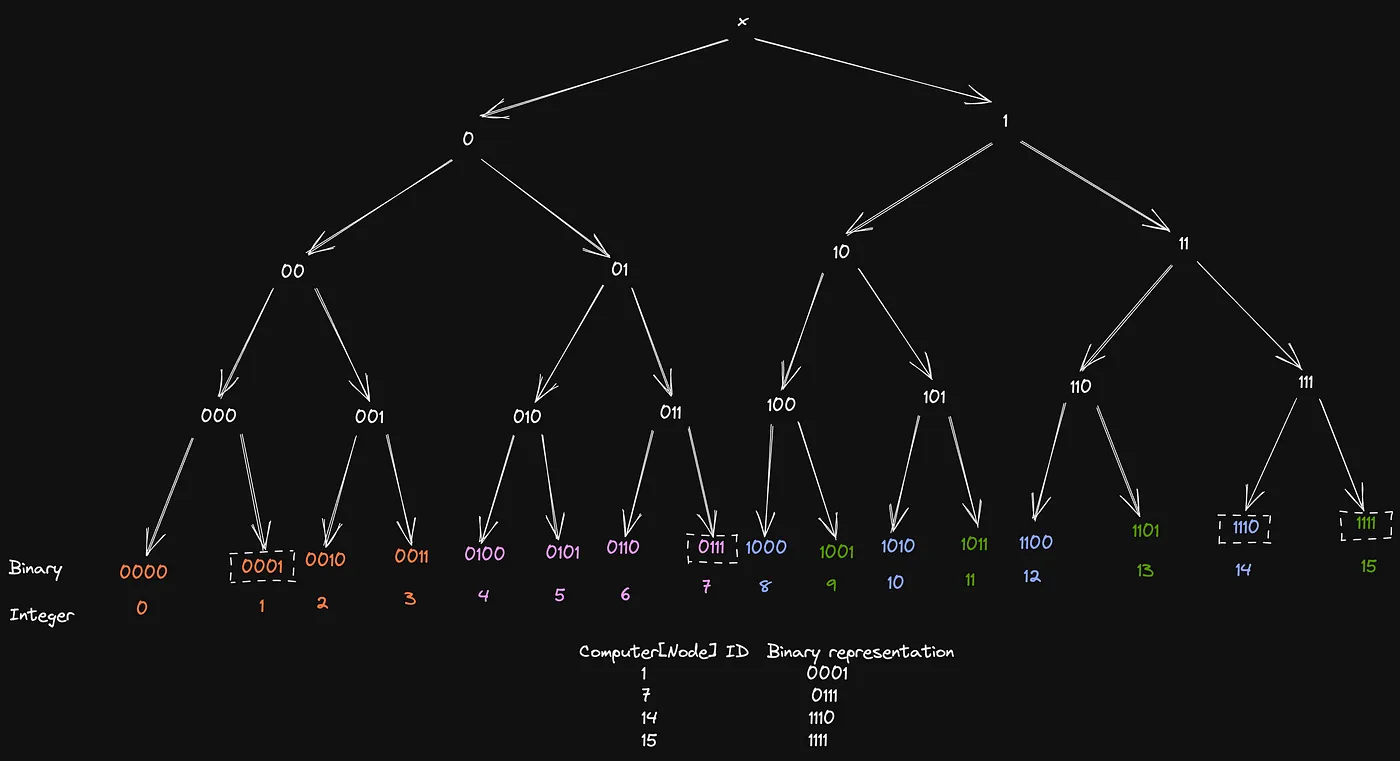

For our example, let’s envision a hash function that maps the keys and nodes to 4 bits instead of 160.

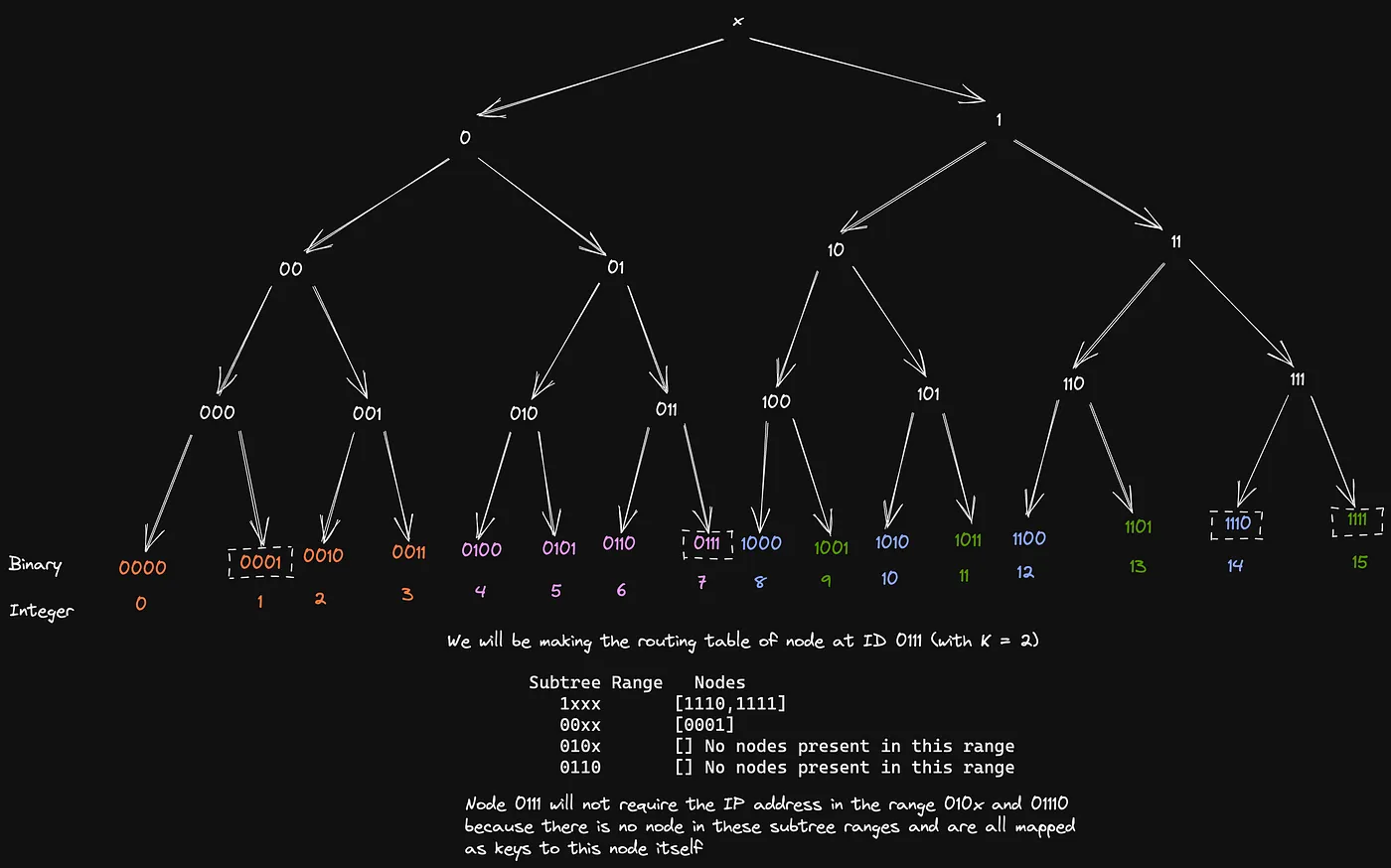

In the following representation, the leaves with boxes around them are the nodes. Let’s assume every other leaf is a key that needs to be assigned to a node. By intuition, you could try assigning the keys to the nodes that have Lowest Common Ancestor [3].

The non boxed leaves are the keys and the keys matching color with a node leaf means the Key is present in that Node.

For nodes 1 and 7, the distribution of keys makes sense, for instance, key “2” is assigned to computer 1 because it shares the LCA tree node [00]. Had leaf 0011 [3] been a node, key “2” would’ve been assigned to it.

But there is a slight issue here, notice that all the keys from 8 to 13 have been assigned to node 14 and none of them to node 15 even though 1110 and 1111 share the same lowest common ancestor with this subset of keys. This is an issue that Kademlia handles very smartly!

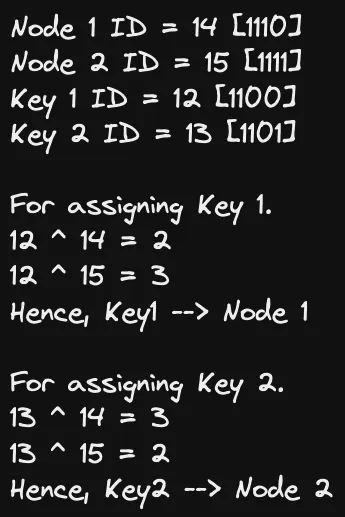

To measure the closeness between two IDs, Kademlia takes the help of the longest common prefix as a heuristic and uses binary XOR to calculate it.

Now, let’s say the IDs of Key, Node1, and Node2 after SHA1 are **k, n1, n2** respectively.

If k XOR n1 < k XOR n2 then the Key will be assigned to Node 1 else the Key will be assigned to Node 2.

Let’s consider how the tie-breaking will work now for distributing the keys 1100(12) and 1101(13) among nodes 14 and 15.

See? now 13 will be assigned to 15 instead of 14! Making the final key distribution to this —

See the beauty of this heuristic? In subtree 1xxx, all the keys and values are equally distributed among the two computer nodes 14 and 15 and hence resolving our first headache!

The K buckets

Moving on, let’s take a look at the next one, how would node 7 find what’s the value at key 13? Kademlia protocol handles this with the concept of “K” buckets.

Every node will have a routing table with IP addresses and IDs of at least “K” other active nodes in a prefix range, but hold up, what exactly does this subtree range mean?

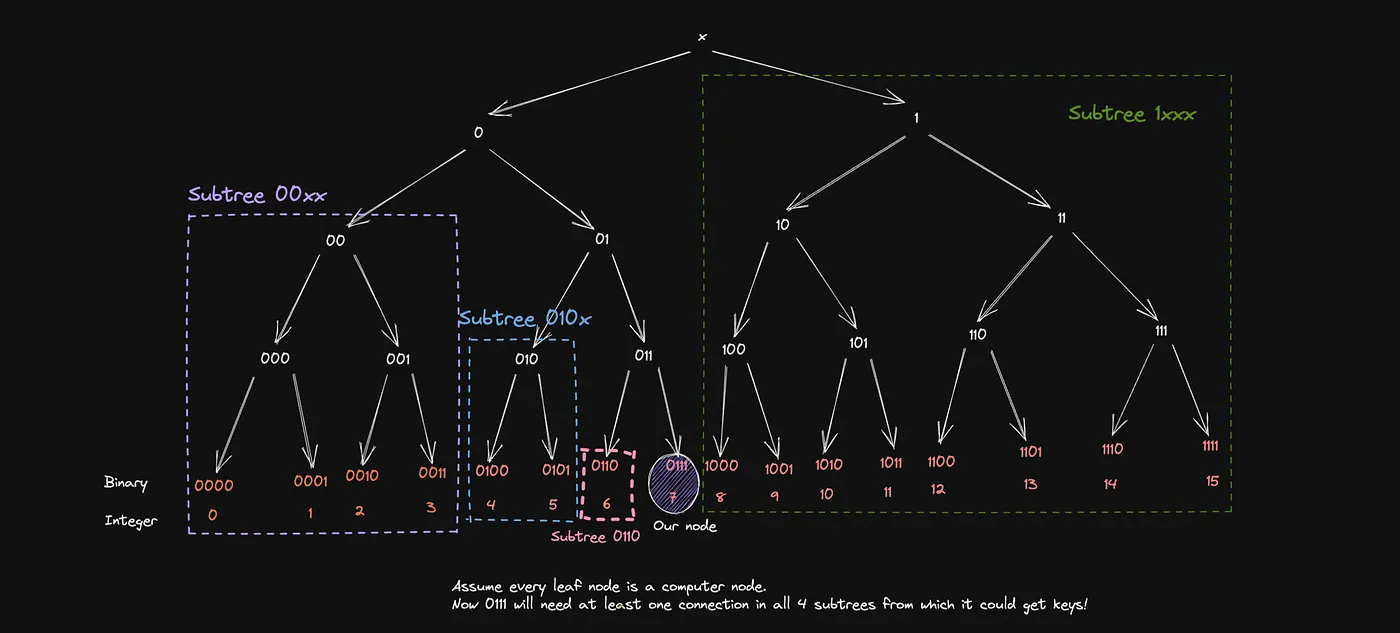

Before we get there let’s try and figure out what is the least number of connections a node, for instance, let’s say Node 7 (0111) will need to fetch any key it needs ASSUMING it has no keys of its own.

A good idea would be to iterate the subgroups of which our node is not part, starting with the Most Significant Bit, 0. This means our node needs to have contact with at least one other node in the subtree 1xxx in case it needs a key format 1xxx .Moving on, the next bit is 1 which indicates that our node needs a contact in 00xx the subtree to fetch a key of a similar pattern. If you check the next bit which is 1 again, it’ll mean our node needs a contact in the subtree 010x to get a key like 0100 . Lastly, our least significant bit, which is 1again signifies that we’ll need the address of 0110 in case it contains a key of its own! Props to Arpit for explaining this beautifully in this subsection of his kademlia video [4].

Ideally, if my hash function maps to N bits, a node will need at least N connections to talk to (Here, N = 4, in actual implementations, N=160). But unfortunately, we are not living in an ideal world, are we? What will happen if the single connection, let’s say node 1011 leaves? What will happen to our dear 0111 if it wants a key in the pattern of 1xxx ?

This is where K buckets help

For every subtree range, a node should have at-most K IP addresses of nodes in this range in its routing table, for the illustration of the same, refer to the diagram below

Now, if our node wants a key let’s say 1101 , it can talk to either 1110 or 1111 and they will give it either the key or the address of the node which contains the key, Hence resolving our headache number 2!

Replication of key

Now that we are done with how to find a key that a node does not have, how to keep multiple replicas of the key so that the data is fault tolerant? This is heavily dependent on whoever is implementing the nodes and what’s their preference, some ideas could be —

- Storing the key in multiple nodes in certain subtree prefixes.

- Storing the key in a quorum format, and needing at least N nodes to acknowledge saving the key.

- Caching the key when fetching for it initially from other nodes and serving the key itself later on.

These are a few and are definitely not limited to this.

In a Kademlia DHT, there are a final few things that piece together the DHT, they are formal RPCs. Quoting this source [5], a node must be able to perform the following 5 RPC calls

A computer can be asked FIND_COMP(id) call and will return k of the closest computer ids in its routing table and their IP addresses.

A computer can receive a FIND_VALUE(key) call and will return the value if the (key,value) pair is stored locally on the machine. If the key is not stored locally, the computer will respond as if it received a FIND_COMP(key) call.

A computer can receive a STORE(key, value) and will just store the key-value pair in a local map of its choice.

A computer can receive a PING call to verify that the computer is still online.

To ensure that keys remain in the network, the caller who stored or requested a resource is required to re-issue a STORE call within a given time frame, such as every 24 hours. Otherwise, computers will automatically evict old key-value pairs to reduce bloat.

That’s about it for this blog, this is the bare bones of how this protocol works, and to think that such an amazing algorithm was just built on top of an XOR heuristic is frankly mind-blowing! Kindly refer to the resources attached below for the references to this material.

Until next time!

Resources

- [1] Kademlia — a Distributed Hash Table implementation to power the overlay network of BitTorrent

- [2] A Guide to Consistent Hashing.-,Consistent%20Hashing%20is%20a%20distributed%20hashing%20scheme%20that%20operates%20independently,without%20affecting%20the%20overall%20system.)

- [3] Lowest Common Ancestor (LCA) in a binary tree

- [4] Routing in Kademlia — Section by Arpit

- [5] Piecing together DHT