The curious case of MongoDB cache evictions

MongoDB is an extremely popular no SQL database solution with an interesting cache architecture. Tons of projects use MongoDB in production including ours at GoTo Financial. It has been working perfectly for quite some time until came to a point when it suddenly wasn’t and this small post is all about our misadventures with MongoDB.

TL;DR

Operational latency spikes occur due to application threads being involved in cache evictions. To avoid the same, increase the eviction workers or the cache triggers involved. Read on to understand the cache structure and workflow in detail.

The incident

Considering that we are a public company, I don’t think I can replicate the RCA in a public blog but let’s try and imagine a close scenario.

Use case

Imagine you are building a small ticket reservations system where you want to keep the tickets saved for long (maybe for showing your users their past flights). You can perform updates on the tickets or create new tickets and maybe delete the tickets after a few months and you are saving all these tickets in some MongoDB collection (call it tickets).

Now, one odd day your monitoring systems start alerting you that your tickets are not being fetched or stored at all!

Debugging the alerts 🕵️♂️

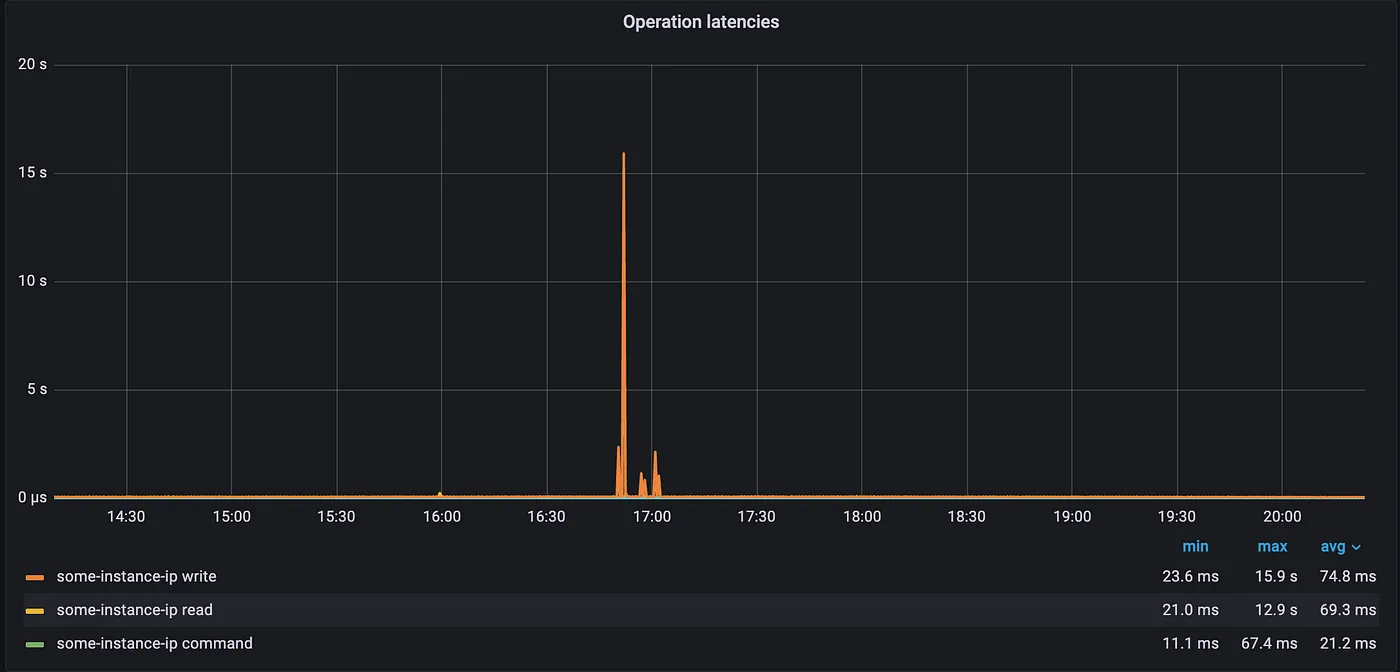

You start digging and find out that you are facing spikes in operational latencies with your operations rising up to whopping 16s!

Why a sudden spike in operational latency? 🤔

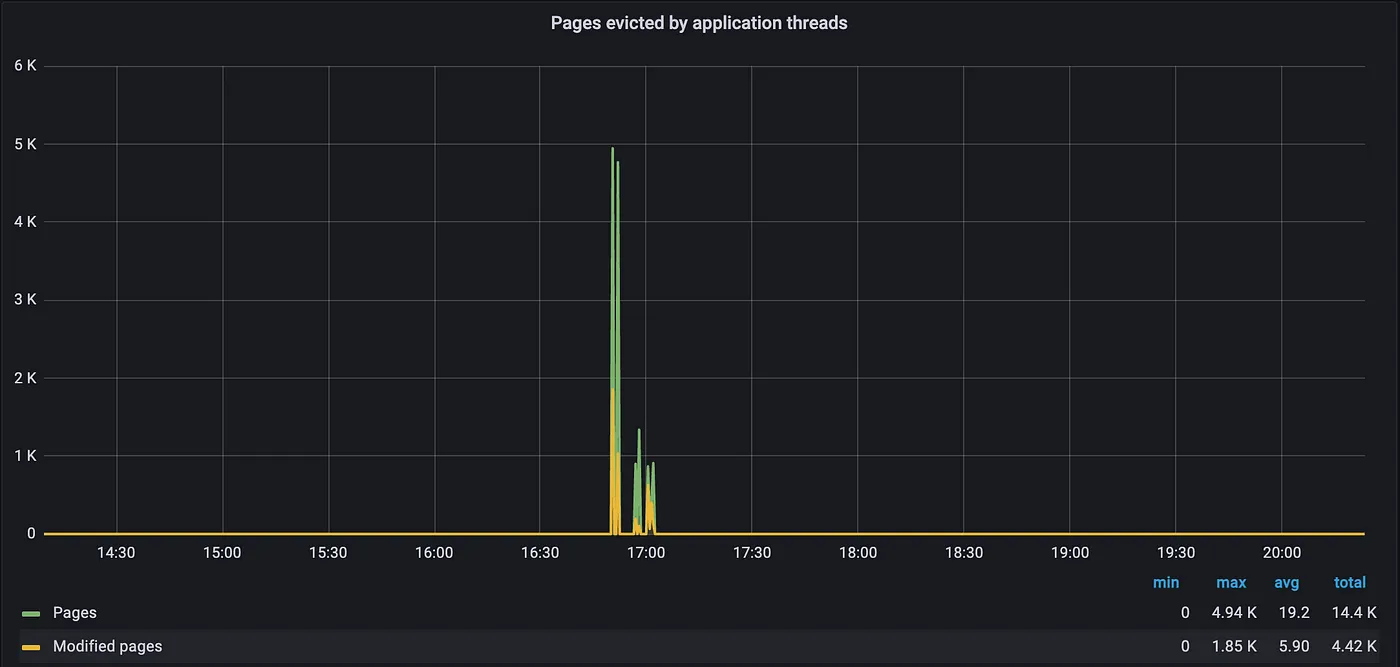

You scour through the rest of the metrics and find out there’s a minor bump coincidentally occurring at the same time as this operational latency, The time overlap and spike patterns are uncanny, this spike in Pages evicted by application threads has to be the culprit!

Alright, but what are these application threads, and why them evicting pages is so chaotic? 🤯

This is the point where I have to introduce wiredTiger[1], it’s MongoDB’s principal database storage engine. This layer decides how to store your collections, fetch them, build indexes around them, cache them, evict the pages from caches, etc, essentially the heart and soul of I/O in MongoDB.

WiredTiger maintains information in the cache for its internal data structures to save / load / manipulate them to support appropriate MongoDB operations.

To evict these pages from the cache wiredTiger has an eviction server that spawns 4 eviction threads pre-configured in MongoDB whose sole responsibility is to maintain wiredTiger’s cache usage at a set of certain targets[2] ( **eviction_target** , **eviction_dirty_target** and **eviction_updates_target**) In contrast, application threads are nothing but threads by MongoDB to perform client operations and serve requests.

Generally, your cache won’t grow to a point where you need to know anything more than this, but alas! your ticket collection wasn’t that lucky.

WiredTiger internally maintains 3 triggers, and if your MongoDB installation triggers any of the conditions, application threads will be pulled in to evict the pages from the cache.

- If the cache bytes stored in wiredTiger cache (which itself is ~50% of the machine RAM[3]) grows to a point that 95% (

**eviction_trigger**)of the WT Cache is occupied. - If the amount of dirty pages in the cache comprises 20% (

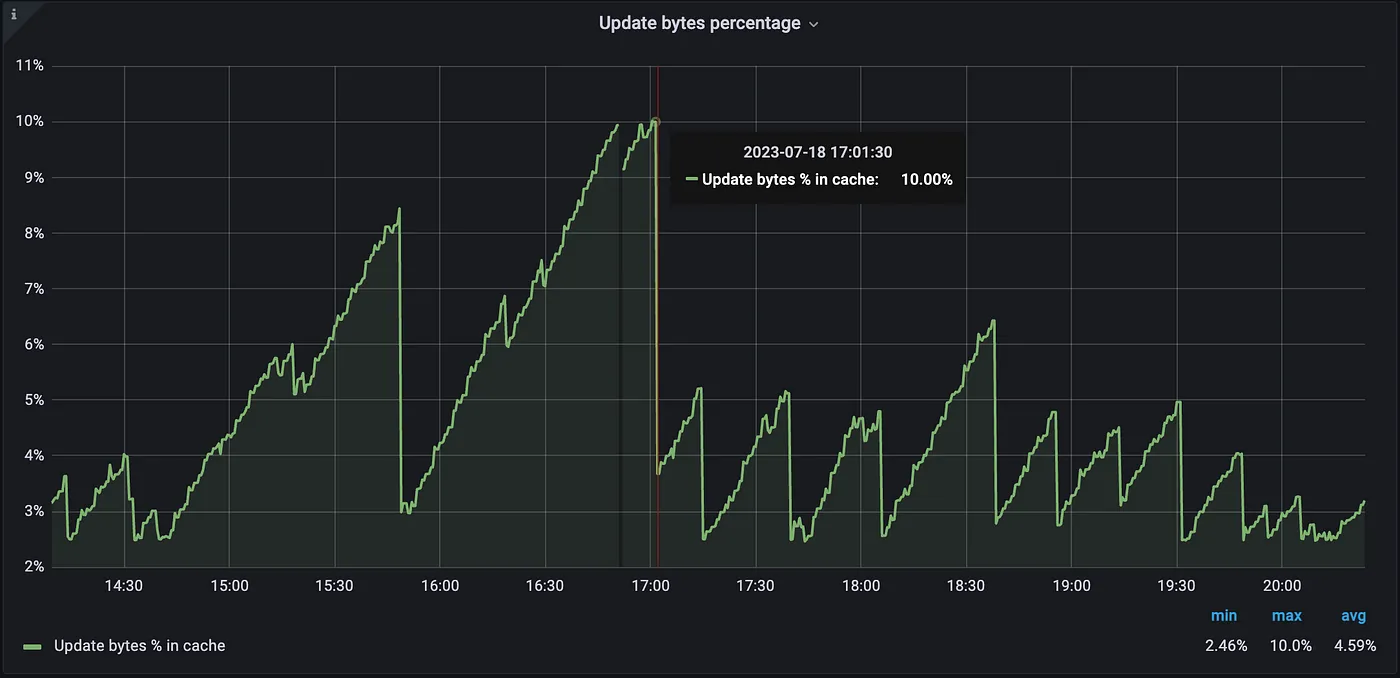

**eviction_dirty_trigger**) of the WT cache. - If the amount of update bytes[4] in the cache comprises 10% (

**eviction_updates_trigger**) of the WT cache.

Let’s suppose our culprit is number 3! Your tickets collection being a write-heavy setup, the insert/update operations were overwhelming the database and the update bytes were intermittently crossing 10.0%-10.1% and then dropping to a lower value after application threads were pulled in.

Why are the update bytes growing that much and not being maintained at their target?

For this, we need to deep dive into the cache maintenance and architecture discussed below:

WiredTiger Cache architecture 🏗 ️

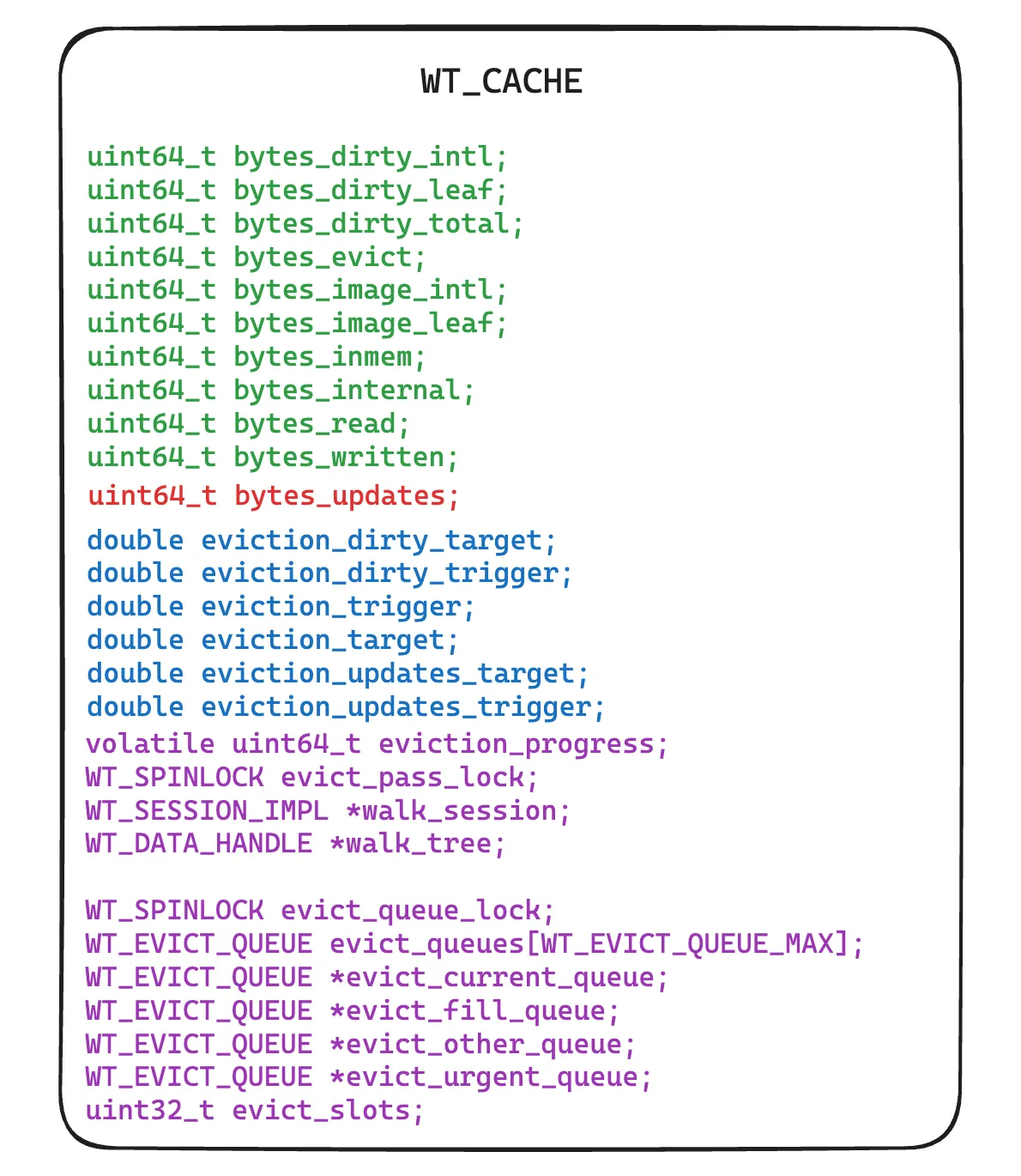

WiredTiger internally maintains a cache in a data structure called __wt_cache[5].

The green variables determine the byte counts of different kinds of pages present in the cache (Note, these are not always accurate and these memory footprints are updated only during B-tree/row/column operations).

The **bytes_updates** is our problem figure.

The variables in dark blue are the targets and triggers derived from configs.

The variables in purple determine the data related to eviction progress:

**evict_pass_lock**,**walk_session**and**walk_tree**are B-tree related locks and sessions from where pages will be populated for eviction**evict_queue_lock**,**evict_queues**,***evict_urgent_queue**etc are the locks and eviction queues in which pages are pushed to be later on evicted by the eviction/application threads.

As mentioned above, only data structures have the ability to change the memory footprint in __wt_cache , so we need to figure out how eviction threads and B-Tree’s cache memory manipulation link together. Let’s find out with the figure given below :

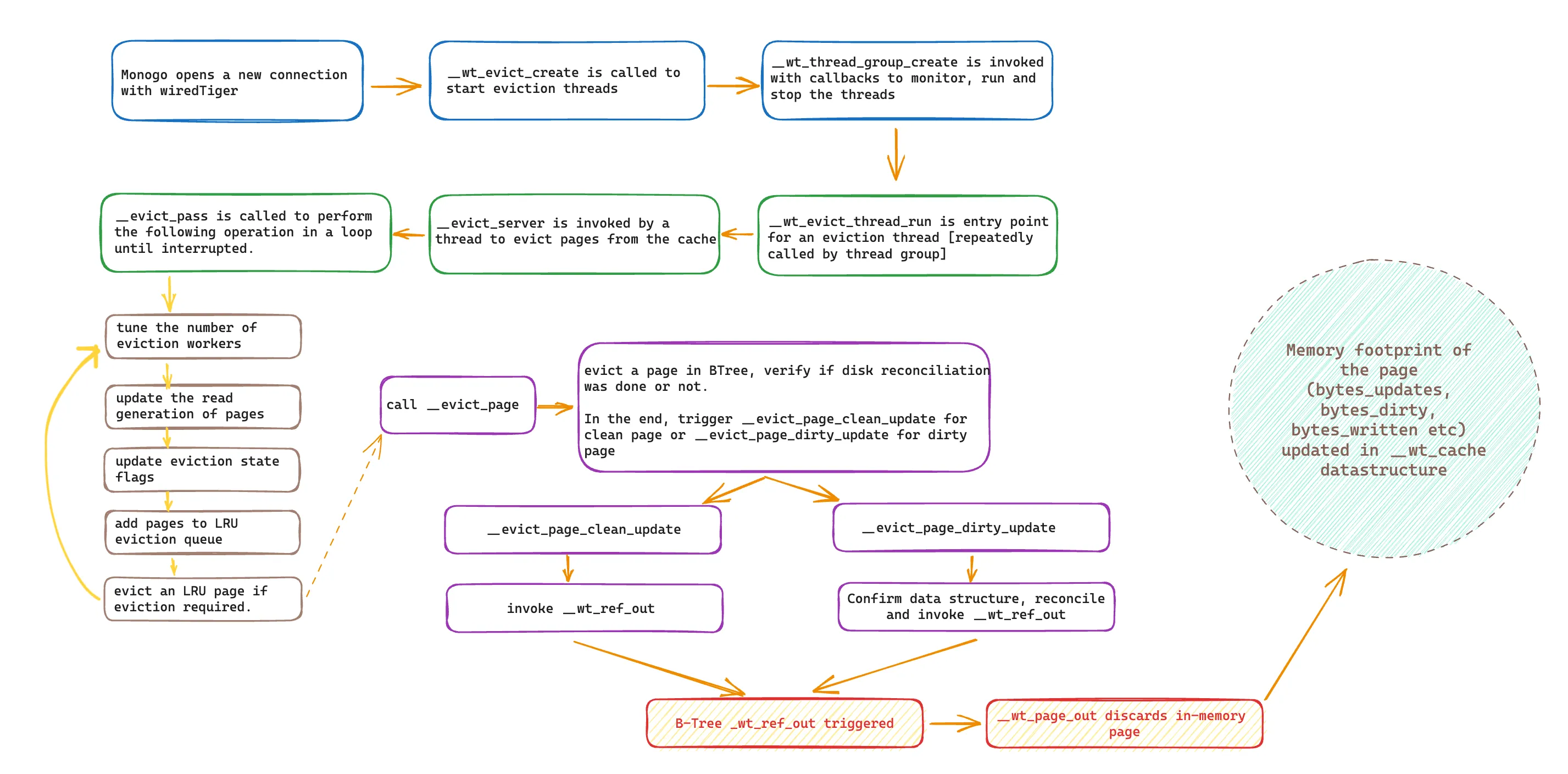

Color coding guide to the above diagram-

- The boxes in blue are the elements that are generally invoked on connection startup.

- Dark green boxes elaborate the function calls invoked by the eviction server to start an eviction thread group and start a thread to begin LRU evictions.

- Brown boxes elaborate the work done by a single thread which spawns multiple workers, adds pages to eviction queues, and finally evicts pages [Note, page addition to queues warrants a separate blog of its own]

- Purple boxes explain what happens when a page is finally picked for eviction.

- The red boxes show where does B-Tree page discard functionality pitch in and update the cache structure!

If we follow the flow given in the above diagram, we’ll reach the __wt_page_out[6] function which is triggered after page eviction. This function is responsible for updating the cache footprint of this page and later on freeing page modification information, both in memory and on disk.

This is how your pages are evicted and memory is freed from the cache. To answer the earlier question we posed that why are update cache percentages not being maintained at their target? There could be multiple scenarios but one hypothesis highly likely hypothesis is:

- Suppose there are > 2 million pages in your cache due to inserts/updates in collections, when LRU eviction walk happens, only 100–200 pages are pushed in the regular queue for eviction. [Again, need a separate blog post to explain how does LRU page queue walk happens]

- Unless more pages are not urgently evicted, it’ll create back pressure on your cache because the write traffic is more or less constant.

- The pages when they are evicted, aren’t guaranteed to have

bytes_updatescomponent associated with them. - Hence the increase in

bytes_updatesis more than the reduction in the same, which keeps growing to a point where B-Trees take the matter into their own hands and evict pages.

Now the question which arises is how to tackle these intermittent operation spikes.

Possible remedies 🧪

- You could try increasing eviction workers from default 4 to a maximum of 20 as described in this percona blog [7].

- You could increase the memory of machine/memory share utilized by wired tiger (not too scalable though).

- You could try and increase the

evict_updates_triggerthe configuration itself to a higher value (although MongoDB does not recommend tuning these configurations, but desperate time calls for desperate measures).

PS: Feel free to drop a better solution to this if you have one :D

Conclusion 😮💨

We discussed in detail an interesting cache eviction issue and discussed its possible remedies while walking through the architecture and design of wired tiger’s Cache and LRU Cache eviction policies.

References 🔗

- WiredTiger — https://source.wiredtiger.com/11.1.0/index.html

- WiredTiger Cache Evictions — https://source.wiredtiger.com/11.0.0/arch-eviction.html#eviction_overall

- WT memory usage — https://www.mongodb.com/docs/manual/core/wiredtiger/#memory-use

- Why track update bytes separately? — https://jira.mongodb.org/browse/WT-6175

__wt_cachestruct in wired tiger — https://github.com/wiredtiger/wiredtiger/blob/develop/src/include/cache.h#L62-L240__wt_page_outmethod to evict the page from B-Tree — https://github.com/wiredtiger/wiredtiger/blob/fe22c23199fd0f6462a148c51b0a9694857a19bc/src/btree/bt_discard.c#L57-L141- Percona blog to tune MongoDB for bulk loads — https://www.percona.com/blog/tuning-mongodb-for-bulk-loads/